Have you ever heard that? The account set out below is based on real life experience – circumstances have been altered to protect the guilty.

Read the full article here

Have you ever heard that? The account set out below is based on real life experience – circumstances have been altered to protect the guilty.

Read the full article here

Niall Reynolds | | LinkedIn, NR Blog |

I recently read a LinkedIn article entitled “Apple will redefine healthcare and make billions” . It made me think of my own industry of Capital Construction and more specifically Project Controls.

We all know the importance of being proactive not reactive when it comes to controlling dynamic Capital Program/Projects. How the opportunities to be effective diminish as the project slides down the Curve of Influence. “Insight better than Hindsight”, etc.

Read the full article here.

“Project Controls – two words at war with one another” so said my companion at a recent meeting of Project Controls experts. “What on earth are you talking about?” I countered. He went on to say that on an exceptionally good day you might have a defined scope, with a finite budget all to be completed within a given time. However well-defined these three elements might be initially they are immediately under threat from the Project Delivery Method, the market and the client’s appetite for CHANGE. Typically for a major Capital Program/Project we bring together all sorts of resources internal/external. Then they are managed by an ad hoc group that will disperse upon Project Completion only to regroup in another part of the industry or world.

Read the full article here.

In 1993 a US Owners Organisation was confronted by a potential large increase in their capital construction volume. It was projected to very quickly exceed $1,000,000 per annum and was likely to continue at that level for the foreseeable future. To respond to this the Owner’s Organisation’s New Construction department formed a strategy to cater for the increase in construction volume with a reduction in lead-time, overall schedule and cost while improving safety and quality.

The lynchpin to this strategy was the alliance of their preferred Designer and General Contractor (GC) to form a separate joint venture legal entity. This legal entity was basically an Engineering, Procurement, Construction and Management (EPCM) company.

The Owner’s Organisation then entered into an EPCM contract with this newly formed entity.

One of main advantages to the Owner’s Organisation was that there was only one contact to be administered. One contract eliminated the perpetual triangular arguments between Owner, Designer and Constructor. Individual projects were to be written as project releases under the one contract regardless of the type or location.

The main advantage to the Designer and Contractor was a steady stream of work without the need to engage in either bidding or marketing.

The criticality of the schedule to the Owner’s Organisation plus the complexity and volatile nature of the project(s) design were such that an Owner ‘hands off’ approach would not be effective. The risk was too great to the Owner’s Organisation. It was their experiences that there was no design-builder in the US market that could provide the flexibility and perform to the standard of the selected Designer and General Contractor alliance. The Projects were complex Hi-Tech facilities and required specialised forms of construction built at a very fast pace and the risk would be too great for a classic designer-builder approach.

The Designer had to be capable of covering all aspects of a dynamic design with in-house resources or by using and managing specialist sub consultants. The Designer had to adapt to constructability reviews from the General Contractor, adjust it’s design schedule and release elements of the design earlier than normal. Likewise, the General Contractor had to be able to self-perform large elements of the work on the critical path as well as act as construction manager (CM). This self-perform advantage should not be underestimated. Many design-builders are really joint ventures of a designer and a construction manager. This EPCM had the capability to, and did, start installation long before plans would have been ready for a typical design-builder to secure bids. The partnering or teaming environment allowed them to do this while mitigating the risks. This approach resulted in greatly reduced our lead times and construction schedules as well as increased safety throughout.

The owner’s construction team and the EPCM team were engaged as soon as a project was authorised. Long before funding had been secured or even sometimes before a site had been selected. There were initial difficulties in breaking down the old triangular relationship. However, as time passed, more of the contractor’s personnel were able to influence the design and more importantly the phasing of the project and associated phasing of the design itself. With this partnering arrangement certain fairly entrenched concepts became blurred. Some of these blurred concepts were:

A way to offset the above lessons would have been to employ third party independent advisors. This was achieved in later hybrids of this contract with the introduction of independent Chartered Quantity Surveyors. However the damage had been done and the partnering Contract with the EPCM was can celled after 5 years. This was despite major World Class advancements in Schedule, Quality and Safety.

It should be remembered that new innovative contracting methods in construction can have far reaching effects that not only affect the manner and length of time to complete a project but also impact how the project is administered. So serious can these impacts be perceived that they outweigh all the improvements in Scope, Schedule, Budget and Safety.

A simple concept that gives a great deal of control over the complex problem of controlling costs on large construction projects

How is it possible to control the cost of something that is not even designed never mind constructed? Far too often the ‘bean counters’ are brought in well after the proverbial horse has bolted. However just as often the construction team are loath to have the ‘bean counters’ involved up front (they do not see the ‘value add’) other than to help them get the Budget approved. Also it must be said that a lot of Finance personnel are reluctant to get involved out of ignorance and sometimes out of fear to share the blame latter on.

Traditional Accountants / CPAs are the ‘undertakers of the commercial world in that they can efficiently tell you what was the cause of death. Estimators need something to estimate from i.e. drawings. Project Controllers are asked to sign up for the future. The seeds of good Project Control are sown well in advance on a project. The Bid Package Cost Code matrix is one of these seeds.

If you have the above two items you then you have the elements of the Matrix. All that remains to do is the following:

The above is a simple example of a budget of 165 being spread over 6 packages of a project. This is so intuitive that I am sure a lot of people, especially construction professionals seeing this, are saying this is just common sense. Well! I ask them to reflect on their past projects and honestly state if anybody on the team utilised such a matrix. I have worked on projects where the costs codes have run to 400 unique cost codes and there were in excess of 150 Design Packages.

Again, I cannot emphasis enough that some Finance person has the Budget broken down into cost codes and some Construction person has the project broken down into something resembling packages.

The creation of the matrix is about 25% of the effort. The real control comes in keeping it up to date and relevant.

If the above is achieved you will have established 75% of the effectiveness of the Bid Package Cost Code Matrix. The remainder and the success lie in

In my experience construction teams do not like the involvement of non engineering staff up front. They see them as somebody else who has to be educated or worse as police men.

A lot of teams argue that they do not need the Matrix as their traditional forecasting by Cost Code is sufficient. Projects are committed by cost codes whole and in part grouped into packages. By concentrating solely on individual cost codes can give a false sense of security. Packages are much more meaningful to the Construction team than individual cost codes. Most modern cost tracking software (especially off the shelf GC packages) if properly used can automatically produce the Matrix. Usually all that is required is the creation of a ‘Dummy Package’ for the Indirects.

Like I have said before all this information is available on the project. However, to be effective as a controlling mechanism the disparate items of information (Finance / Construction) need to be brought together and the Matrix is a means to this end.

Niall M Reynolds has spent his career working on large international construction programs in the Petrochemical, Public Infrastructure, Leisure and Semi-Conductor industries. In this article he provides an overview of the challenges that can arise in the area of Contract Administration of such programs.

Contract Administration for Super Projects or Programs

What has prompted me to write this article is my awareness of how in certain circumstances the benign and sometimes ‘taken for granted’ aspects of Contract Administration can become a ‘showstopper’ on major construction programs.

A common understanding is that Contract Administration means the non-technical aspects of the program (the technical aspects being Design, Health and Safety, Estimating, etc.). Some examples of the non-technical aspects are Draw-down of Funds, Change Management, Payments, Commercial Close Out and Reporting.

On small and less complicated domestic projects these activities are typically executed by any or a combination of the Project Manager, Main Contractor, Engineer, Architect, QS and other members of the project team. All the contracting parties, within a region or industry are usually familiar with one another and with local forms of contract, practice and precedent. Sometimes there is a history of having worked together on previous, similar projects. Contracts in this case, if similar to their previous and hopefully successful experiences, take on a less influential role in shaping outcomes

However, on large, one-off, construction programs this is typically not the case and failure to anticipate, innovate and manage these non-technical activities can jeopardise the whole endeavour. Companies, organisations and people have to very quickly learn to work together for a successful outcome against an unforgiving ‘ticking clock’. As one project manager said to me once, “If you don’t work out your difficulties now, you are sure to fight over them later!”.

I have seen valuable, finite, resources diverted from an already stretched program team to form taskforces, swat teams, etc., to solve administrative type issues. Regularly these teams find that many of the issues could have been avoided with focused attention at the planning stage of the program. One of the main problems is that Contract Administration is very often the last thing on anybody’s mind at program inception and yet the Contract is usually the first place people go to look for remedies when performance does not match expectations.

One of the impacts of globalisation is the creation of larger, more complex multi-layered, cross-cultural, and international, construction programs. These programs because of their international location are already aggravated by

Very often, time is of the essence on these programs because of the need to be first to market with a new product or process. Although a construction program could exceed a billion US dollars it may still be only a portion of the total capital being invested (sometimes less than a third). Private clients can be very impatient and frustrated by the length of time construction takes. Therefore, this type of program usually tends to be executed at breakneck speed. These clients demand predictable results to enable their business goals. This is all the more reason not to have the program jeopardised by something as benign or as fixable as Contract Administration.

Typical Program

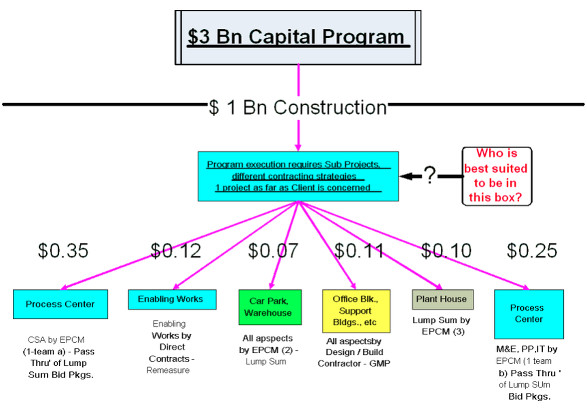

A private corporation wants to invest $3,000,000,000 of capital in a new process or product, $1,000,000,000 of which is for the construction of the 100,000 m2 manufacturing or processing facility and support buildings. It secures the services of a world class Engineering Procurement Construction Management (EPCM) firm. Typically there will be ~18 to 24 months for Design and Construction. There are few organisations that have the resources to manage the entire program from conception to completion. Therefore, a consortium is assembled to execute the program. More and more, these consortia are drawing from a global resource pool for management, labour, materials and equipment manufacturers. Program and Project Team meetings can have as many nationalities as participants representing Clients, Consultants, Contractors and Suppliers.

At the outset the team is very often extremely challenged from an engineering design point of view. At program inception what is driving the priorities of the team is the amount of time and money that is available for Design & Construction. The last thing on their minds is to plan for the impact of the program structure on Contract Administration.

In order to get a ‘jump’ on the schedule, an enabling contract is usually let as soon as possible to demolish existing structures, clear the site, commence basic foundations and site works, etc.,. In parallel, contracts are let to commence programming and conceptual design. In addition to the primary processing facility there will be ancillary type structures (office blocks, warehouses, multi storey car parks, central utility plant buildings, etc.). These being somewhat simpler to construct might be awarded as Design Build or the more traditional Design, Bid, Build Lump Sum Contracts. Sometimes they are awarded to and managed by another competitive EPCM(s) in parallel. Another twist is that some of the ancillary sub-projects may be located many kilometres away from the main activity.

See Figure 1 for a diagram of how this Contract Strategy might look.

It is not my intention to say “who is the best suited” to manage and co-ordinate the Contract Administration of the Program. It is “horses for courses”. My point is that it needs to be given due consideration at the time of Program Inception. I have seen the role ably performed by

If for example, the overall management and co-ordination of the Contract Administration of the Program is given to the lead EPCM firm, this can lead to problems of potential conflict of interest, lack of trust and confidentially issues arising between parties who may be keen competitors outside of the program.

Every EPCM firm has its own ‘in-house’ procedures manual on how to successfully execute large complicated construction programs. On the above program there could possibly be 3 such manuals in conflict or vying for supremacy. There is the question of trying to accommodate the different execution methodologies of each sub-project. For example, it may well be mandated by the lead EPCM’s procedures manual to request Daily Manpower and Physical Progress reports by trade and by location. Under certain forms of contract this will be inappropriate. Likewise, each entity will have its own IT systems and various Business and Project Management Systems of record that they are mandated to use.

Even more important than the impact of the above structure on the various Construction Managers, Consultants and Management Contractors is the impact on the Trade Contractors and Suppliers who, after all, have to do the actual work. Theoretically, the same Trade Contractor and Supplier could be working on any or all 6 of the different sub-projects depicted above. Imagine their confusion if the basic aspects of administration differ from sub-project to sub-project on the same Program.

Typical impact and solution.

There are many examples of how the layering of different contracting entities can impact the Draw-down of Funds, Change Management, Payments, Commercial Close Out and Reporting etc. However, in the interest of space, only how Payments were affected on an actual Program is briefly outlined here.

The program was averaging 72 days from request of payment to actual receipt of funds. In some parts of the world that might appear to be more than adequate but in this particular location, 30 days was the industry practice and expectation. (This is another example of how location can impact on elsewhere-accepted practices and how otherwise standard corporate operating procedures might have to be adjusted).

After investigation and some business process re-engineering, the cycle was reduced to 19 days without any compromise to the standards of review. Most of the re-engineering involved the removal of duplicate approvals. A twice-monthly payment cycle was effortlessly introduced. During the process, a mechanism was discovered and agreed, whereby exceedingly large sums of money could be paid within 10 days if suitable discounts were offered thereby bringing a commercial incentive to the Client very often lacking in the more traditional approaches. How much better would it have been for all concerned if the program payment process had been aligned before it got to 72 days?

Principles similar to these can be applied to the management of RFIs, Submittals, Document Control and all manner of program reporting. The same type of problems occur, and similar personnel are involved.

Conclusion

Complex, multi-layered, cross cultural, international, construction programs are managed by a group of ‘once-off’ contracted parties with their ‘canned’, inherited, processes and systems that come together only for a finite period of time. Their failure to consider this and other unique aspects of the program’s structure on Contract Administration from day one can unnecessarily jeopardise the whole enterprise.