Niall M Reynolds has spent his career working on large international construction programs in the Petrochemical, Public Infrastructure, Leisure and Semi-Conductor industries. In this article he provides an overview of the challenges that can arise in the area of Contract Administration of such programs.

Contract Administration for Super Projects or Programs

What has prompted me to write this article is my awareness of how in certain circumstances the benign and sometimes ‘taken for granted’ aspects of Contract Administration can become a ‘showstopper’ on major construction programs.

A common understanding is that Contract Administration means the non-technical aspects of the program (the technical aspects being Design, Health and Safety, Estimating, etc.). Some examples of the non-technical aspects are Draw-down of Funds, Change Management, Payments, Commercial Close Out and Reporting.

On small and less complicated domestic projects these activities are typically executed by any or a combination of the Project Manager, Main Contractor, Engineer, Architect, QS and other members of the project team. All the contracting parties, within a region or industry are usually familiar with one another and with local forms of contract, practice and precedent. Sometimes there is a history of having worked together on previous, similar projects. Contracts in this case, if similar to their previous and hopefully successful experiences, take on a less influential role in shaping outcomes

However, on large, one-off, construction programs this is typically not the case and failure to anticipate, innovate and manage these non-technical activities can jeopardise the whole endeavour. Companies, organisations and people have to very quickly learn to work together for a successful outcome against an unforgiving ‘ticking clock’. As one project manager said to me once, “If you don’t work out your difficulties now, you are sure to fight over them later!”.

I have seen valuable, finite, resources diverted from an already stretched program team to form taskforces, swat teams, etc., to solve administrative type issues. Regularly these teams find that many of the issues could have been avoided with focused attention at the planning stage of the program. One of the main problems is that Contract Administration is very often the last thing on anybody’s mind at program inception and yet the Contract is usually the first place people go to look for remedies when performance does not match expectations.

One of the impacts of globalisation is the creation of larger, more complex multi-layered, cross-cultural, and international, construction programs. These programs because of their international location are already aggravated by

- Local industry and business practice differences

- Language difficulties within Project Teams and the workforce

- Cultural differences that impact behavioural relationships

- Currency fluctuations in the world market

- Time zone and physical distance

- Infrastructure differences (e.g. broadband, electricity, roads, etc)

Very often, time is of the essence on these programs because of the need to be first to market with a new product or process. Although a construction program could exceed a billion US dollars it may still be only a portion of the total capital being invested (sometimes less than a third). Private clients can be very impatient and frustrated by the length of time construction takes. Therefore, this type of program usually tends to be executed at breakneck speed. These clients demand predictable results to enable their business goals. This is all the more reason not to have the program jeopardised by something as benign or as fixable as Contract Administration.

Typical Program

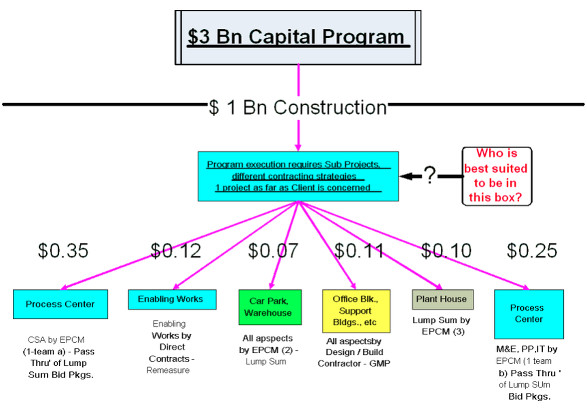

A private corporation wants to invest $3,000,000,000 of capital in a new process or product, $1,000,000,000 of which is for the construction of the 100,000 m2 manufacturing or processing facility and support buildings. It secures the services of a world class Engineering Procurement Construction Management (EPCM) firm. Typically there will be ~18 to 24 months for Design and Construction. There are few organisations that have the resources to manage the entire program from conception to completion. Therefore, a consortium is assembled to execute the program. More and more, these consortia are drawing from a global resource pool for management, labour, materials and equipment manufacturers. Program and Project Team meetings can have as many nationalities as participants representing Clients, Consultants, Contractors and Suppliers.

At the outset the team is very often extremely challenged from an engineering design point of view. At program inception what is driving the priorities of the team is the amount of time and money that is available for Design & Construction. The last thing on their minds is to plan for the impact of the program structure on Contract Administration.

In order to get a ‘jump’ on the schedule, an enabling contract is usually let as soon as possible to demolish existing structures, clear the site, commence basic foundations and site works, etc.,. In parallel, contracts are let to commence programming and conceptual design. In addition to the primary processing facility there will be ancillary type structures (office blocks, warehouses, multi storey car parks, central utility plant buildings, etc.). These being somewhat simpler to construct might be awarded as Design Build or the more traditional Design, Bid, Build Lump Sum Contracts. Sometimes they are awarded to and managed by another competitive EPCM(s) in parallel. Another twist is that some of the ancillary sub-projects may be located many kilometres away from the main activity.

See Figure 1 for a diagram of how this Contract Strategy might look.

It is not my intention to say “who is the best suited” to manage and co-ordinate the Contract Administration of the Program. It is “horses for courses”. My point is that it needs to be given due consideration at the time of Program Inception. I have seen the role ably performed by

- Client’s in-house Construction Group

- Program Consultants acting as Client Representatives

- One of the EPCMs

- Management or Prime Contractor

If for example, the overall management and co-ordination of the Contract Administration of the Program is given to the lead EPCM firm, this can lead to problems of potential conflict of interest, lack of trust and confidentially issues arising between parties who may be keen competitors outside of the program.

Every EPCM firm has its own ‘in-house’ procedures manual on how to successfully execute large complicated construction programs. On the above program there could possibly be 3 such manuals in conflict or vying for supremacy. There is the question of trying to accommodate the different execution methodologies of each sub-project. For example, it may well be mandated by the lead EPCM’s procedures manual to request Daily Manpower and Physical Progress reports by trade and by location. Under certain forms of contract this will be inappropriate. Likewise, each entity will have its own IT systems and various Business and Project Management Systems of record that they are mandated to use.

Even more important than the impact of the above structure on the various Construction Managers, Consultants and Management Contractors is the impact on the Trade Contractors and Suppliers who, after all, have to do the actual work. Theoretically, the same Trade Contractor and Supplier could be working on any or all 6 of the different sub-projects depicted above. Imagine their confusion if the basic aspects of administration differ from sub-project to sub-project on the same Program.

Typical impact and solution.

There are many examples of how the layering of different contracting entities can impact the Draw-down of Funds, Change Management, Payments, Commercial Close Out and Reporting etc. However, in the interest of space, only how Payments were affected on an actual Program is briefly outlined here.

The program was averaging 72 days from request of payment to actual receipt of funds. In some parts of the world that might appear to be more than adequate but in this particular location, 30 days was the industry practice and expectation. (This is another example of how location can impact on elsewhere-accepted practices and how otherwise standard corporate operating procedures might have to be adjusted).

After investigation and some business process re-engineering, the cycle was reduced to 19 days without any compromise to the standards of review. Most of the re-engineering involved the removal of duplicate approvals. A twice-monthly payment cycle was effortlessly introduced. During the process, a mechanism was discovered and agreed, whereby exceedingly large sums of money could be paid within 10 days if suitable discounts were offered thereby bringing a commercial incentive to the Client very often lacking in the more traditional approaches. How much better would it have been for all concerned if the program payment process had been aligned before it got to 72 days?

Principles similar to these can be applied to the management of RFIs, Submittals, Document Control and all manner of program reporting. The same type of problems occur, and similar personnel are involved.

Conclusion

Complex, multi-layered, cross cultural, international, construction programs are managed by a group of ‘once-off’ contracted parties with their ‘canned’, inherited, processes and systems that come together only for a finite period of time. Their failure to consider this and other unique aspects of the program’s structure on Contract Administration from day one can unnecessarily jeopardise the whole enterprise.